Burrowing Preference

Introduction

Mictyris longicarpus or more

commonly referred to as the light-blue solider crab is an iconic, endemic species

to the Eastern coast of Australia (Davie, 2011). Largely popular among the

public due to their trek up the beach at low tide that entire populations

simultaneously embark upon (Cameron, 1966). A study has been conducted on M.

longicarpus distribution and burrowing preference along a longitudinal

gradient in regards to topography of an intertidal sand flat, this study found

topography to be one many factors affecting the distribution of solider crab

burrows (Rossi & Chapman, 2003). Other factors they hypothesized to be

further affecting the distribution of burrows was sediment composition,

moisture, food abundance and also the behavioral and perceptiveness of each individual

crab (Rossi & Chapman, 2003).

Various beaches and intertidal habitats within the Moreton Bay region have been highly

manipulated and degraded by human development. Significant areas of mangrove

forest have been cleared to create beaches. Along parts of the coastline in Scarborough, sections of mangrove forest are still intact, right next to sheltered sandy beaches. M. longicarpus

appears to be only found along the beach and not in the mangrove forest, while literature has stated that both environments are suitable habitat

(Cameron, 1966). While

observational studies allow one to truly discern natural behavior and ecology, they

have the draw backs of confounding variables and correlations. In a highly

controlled environment I wanted to determine what factor was causing the

population of solider crab from not taking up residence in the mangrove forest,

which compared to the sandy beach, is less disturbed from humans and dogs and

also more inconspicuous to shore bird predators. As speculated in Rossi & Champman (2003), composition of sediment would play a role in preference of substrate, I aimed to develop this theory further, so all other variables were limited. Although M. longicarpus

is known to live in mangrove forest environments (Cameron, 1966), I hypothesized

that they would have a preference of the intertidal sandy substrate to the low

oxygenated, dense, highly moist sediment of the mangrove forest.

Method

10 M. longicarpus species were dug up from their burrows

at a sheltered sandy beach in Scarborough, Queensland Australia. Sediment from the same beach was gathered and

sediment from a small mangrove forest 800m down the shore was also gathered.

Figure 1: Left: The small mangrove forest where the mangrove sediment was sourced from. Right: The sheltered sandy beach where the sandy sediment was sourced from and where the M. longicarpus specimens were sourced from. Both locations are situated in Scarborough, QLD Australia and are along the strip line of coast approximately 800m apart. Original photo taken by Kate Buchanan, 2014.

Half of a fish tank was filled

with substrate from the mangrove forest and the other half was filled with

substrate from the sandy beach habitat. The ten M. longicarpus species were

placed in the center of the fish tank where the two different sediments meet. The

crabs were left to burrow and after approximately 6hrs, the time it would take

for another low tide to occur, it was recorded in what substrate the crabs had

burrowed in. This was repeated 3 times.

Figure 2: The fish tank upon which 10 M. longicarpus crabs were released, after approximately 6 hours location of burrowed crab was recorded, this process was repeated 3 times.The tank is half filled with mangrove sediment(right) and sandy beach sediment (left). Original photo taken by Kate Buchanan 2014.

Results

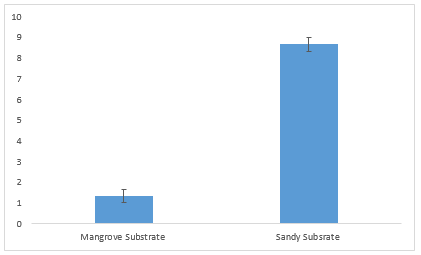

The results are summarized in Figure 1. The first replication

found one crab had burrowed in the mangrove substrate while nine crabs had

burrowed in the sandy substrate. The second replication found two crabs had

burrowed in the mangrove substrate while eight crabs had burrowed in the sandy

substrate. The third replicate found that one crab had burrowed in the mangrove

substrate while nine crabs had burrowed in the sandy substrate. As shown by the

difference in standard error bars in Figure 1, there is a significant difference

and therefore a preference displayed towards burrowing in the sandy substrate.

Figure 3: The mean of three replicate of M. longicarpus’ burrows in sediment

attained from a mangrove forest (Mangrove Substrate) compared to sediment

attained from a sandy foreshore environment (Sandy Substrate). On the Y axis is number of crabs and the X axis is type of sediment. Sample size of

ten per trial.

Discussion

The results show that M. longicarpus had a preference to burrow in the beach sediment

than the sediment found in the mangrove forest. Replications were used to gather more data and

increase sample size, but also to determine whether solider crabs would change

their preference- to see if the familiarity of the beach sand was the only

reason for their preference. If this was the case I would expect to see an increase

of preference to mangrove sediment as over time individual's would become more bold with their surroundings. This was not the case as no increase of preference to mangrove sediment appeared in the results.

My

hypothesis was confirmed that M.

longicarpus would show a preference to the sandy beach sediment. One potential reason as to why there is a

preference to the sandy substrate could be the moisture content. Rossi & Chapman (2003)

found that M. longicarpus preferred to burrow in depressions rather than

humps. They attributed this result to greater amounts of organic debris around depressions (a

potential food source) and an increase in moisture within the depression sediment. They believed the preference to sand with an increase in moisture

was due to the fact that solider crabs need water to feed and moist sand also creates a softer substratum to burrow in (Rossi & Chapman, 2003). A study

conducted by Hartnoll (1973) on the Thailand burrowing crab Dotila

fenestrata which has a similar cyclicity and behaviour to M. longicarpus,

found that distribution of burrows was affected by drainage of the substrate.

Where the mangrove forest was not well drained crabs were not found (Hartnoll,

1973). Perhaps this is the case for M. longicarpus with the mangrove sand being

dense with a higher content of moisture. The thick waterlogged nature of the

mangrove sand with its high fluidity, may have made it more difficult for the

obligate air breather to build the igloo like structure required to breathe air

from underneath the ground. However it is clear that it is not impossible for

M. longicarpus to burrow in this sediment as populations are found in mangrove

forests (Cameron, 1966) and few solider crabs chose to burrow in mangrove

sediment in this experiment. I assume that the choice of substrate did not have

anything to do with food as mangrove sediment is rich in organic matter (Hartnoll,

1973). Further analysis is required to determine the characteristic of the

mangrove sediment that causes a preference against it for a sandy sediment in

the M. longicarpus species.

|